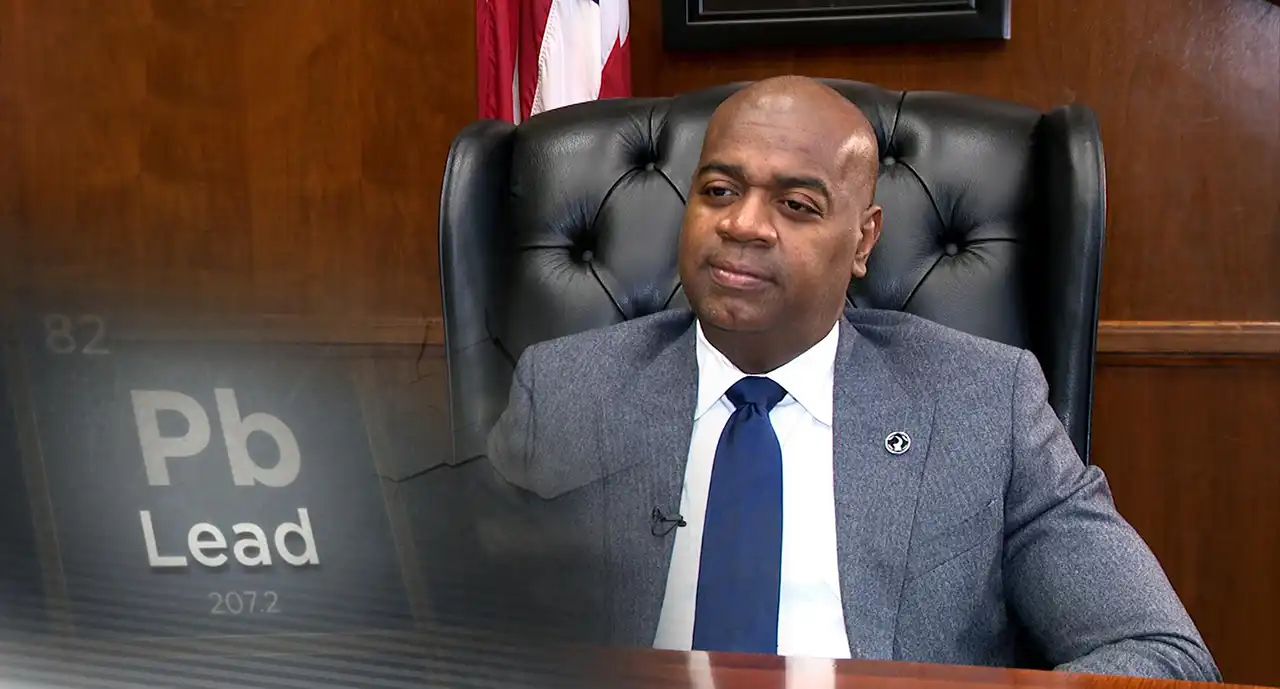

Kareem Adeem remembers a conversation with Mayor Ras J. Baraka in 2017 when the city showed its first lead in water levels exceeding regulatory standards in residential homes in 25 years.

Adeem was then the assistant director of the Newark Water & Sewer Department and the mayor asked him what they could do to fix the problem. “I explained a new corrosion control system would solve the problem, but the only way to fix it permanently would be to remove all the lead service lines and replace them with copper,” Director Adeem said.

“He asked, ‘How much will it cost?’”

“I said, ‘About $190 million dollars.’

“And he said, ‘Get it done.’”

Adeem, now director of the renamed Newark Water & Sewer Utility, said ‘Get it done’ became the unofficial motto of Newark’s unprecedented lead-line replacement program, which has been held up as the national model for cities and towns hoping to extract their dangerous lead service lines.

But before one shovel broke the pavement, Mayor Baraka had to lay important legal and financial groundwork. While the mayor prepared to create a $75 million bond to begin a 10-phase program to fix 1,500 lead lines per phase, he faced an obstacle of using public money on private property. “Service lines are the responsibility of the homeowner,” Adeem said. “The mayor asked the Essex County legislative team to help him get over that obstacle. The late state Sen. Ron Rice and Assembly women Teresa Ruiz and Eliana Pintor Marin pushed forth a bill to allow Newark to use the bond money specifically for lead line repairs. The legislation was groundbreaking and two years later, Gov. Murphy signed a statewide bill.

When the city launched the first phase of the lead line replacement program, it quickly learned of two more significant obstacles. First, some residents balked at the $1,000-$2,000 construction fee the state asked the city to charge each resident to have their lead line replaced. “We heard from some homeowners who said things like, ‘I’ve been drinking this water for 50 years, and nothing’s wrong with me,’” Adeem recalled. Second, in a city where about 75 percent of residents rent, Newark quickly realized tracking down landlords would be time consuming and an inefficient way to tackle such a large project. “Mayor Baraka was very astute at understanding these legal obstacles and willing to take them on,” said Tiffany Stewart, an attorney who was then the Assistant Director of Water & Sewer Department. “He took a dynamic and progressive approach to not kick the problem down the road and make a permanent change for future generations.”

At Mayor Baraka’s urging, the Newark City Council passed two ordinances to make the full-scale project possible. Bolstered by an $120 million bond supported by Essex County, the council made the lead line replacement mandatory and free. “No one paid to get their lead line replaced,” Adeem said. “Not even the first people we were supposed to charge.” The second municipal law allowed the city to enter private property without the owner’s permission, allowing the city to take a street-by-street, block-by-block approach to eventually finish all 23,190 lines in less than three years. You have to give all credit to the mayor,” Adeem said. “He thought outside-the-box. When we hit obstacles, we removed them. He had the political will, and political muscle to get it done.”